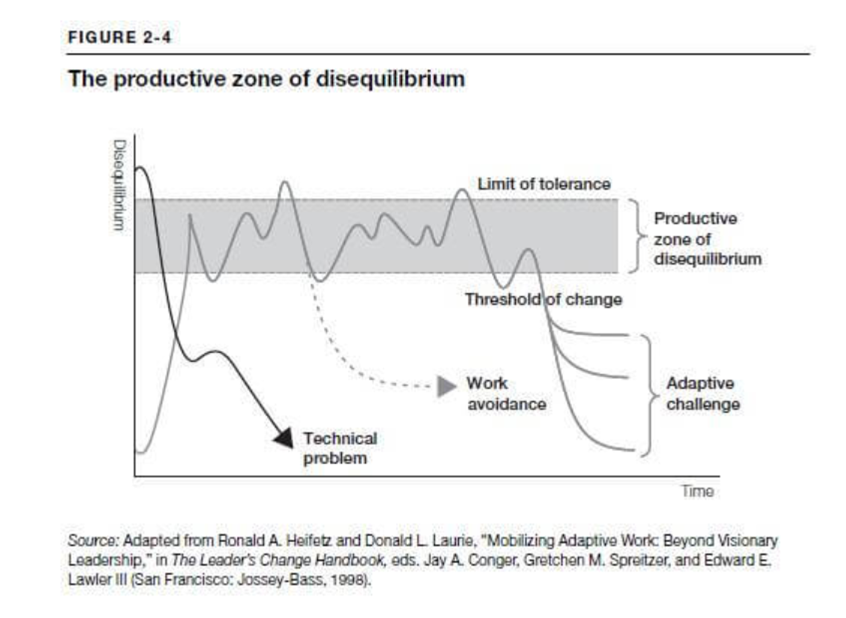

Have you seen this diagram? It may look complicated at first glance, but it’s actually rather simple, and understanding it can be enormously helpful to anyone leading an organization, including ministry leaders.

I first encountered this diagram in a book called, The Practice of Adaptive Leadership, by Heifetz, Grashow, and Linsky (a book I cannot commend strongly enough). In the diagram, technical problems are those problems that even when complex are relatively easy to identify and define, and which call for answers and resources that are readily available. Adaptive challenges take place at a deeper level with broader implications, require learning among everyone involved, and call for solutions that may require significant shifts in the organization’s values and patterns of behavior. Simply put, technical problems generally don’t require people to change; adaptive challenges generally do (including you!).

If you’re like me, the tendency is to quickly and effectively address all the short-term technical problems that emerge. So be it. But if this is all we spend our time doing, not only are we not working on long-term adaptive challenges, we’re actually dismantling the environment where adaptive leadership can thrive. In other words, spending all our time solving technical problems is not just a failure to adaptive leadership; it’s working against adaptive leadership. If the life of the organization becomes too static, and people are too comfortable and satisfied with technical problems having quick solutions, then it is very difficult for the organization to go where it needs to go. Without some sort of disequilibrium and adaptive change, organizations tend to plateau and eventually die.

One challenge, then, is knowing how and when to generate disequilibrium by exposing a conflict in assumed values, naming the elephants and sacred cows, doing anything that inherently take people out of their comfort zones and challenging them to see themselves and the world differently. The other challenge is to keep this disequilibrium in a zone where change is possible but not pushed to the point where everything falls apart. This delicate work is often difficult but vitally important. Heifetz et al liken it to a pressure cooker: “set the temperature and pressure too low, and you stand no chance of transforming the ingredients in the cooker into a good meal. Set the temperature and pressure too high, and the cover will blow off the cookers top, releasing the ingredients of your meal across the room” (29).

Sometimes the “pressure cooker” is gift wrapped and delivered to us, and our first instinct is to get rid of it. Why waste such a great gift? When there’s disequilibrium, whether unanticipated or intentionally, let’s take advantage of it. What are the changes you’ve been eager to implement but haven’t found the right time to do so? What are some of the new things you’ve been wanting to try in worship, mission, or in other avenues of congregational life? What are the programs that are in desperate need change, improvement, or removal? Why not make those changes now while there’s disequilibrium? And, in terms of long-term adaptive challenges, how can these changes draw attention to the larger underlying issues that are preventing necessary change and adaptation? How can you jumpstart some critical conversations in your congregation?

Because the church is called to be adaptive in its faithfulness to the world, we should always be in some sort of disequilibrium. The Holy Spirit is always leading us to people, places, and in ways that discomfort, disrupt, and dismantle. Let’s not be surprised by that reality and the opportunities it affords.

No Comments